Most of us have encountered a situation where we can’t help but wonder why the subtitles on the screen don’t quite match the words spoken. ‘Didn’t he say something different?’ and ‘But I’m sure she said more than just that!’ are only two examples of such occasions. What makes some lines more important than others in a meaningful conversation?

How does a translator create subtitles for a film or television series, or any other video for that matter? Adding subtitles to a video file requires the availability of a suitable computer program. It indexes the audio track for the video being subtitled, and the subtitles are slotted in accordingly. This produces a text file of the subtitles timed for the video and audio both. One application used for the task is Subtitle Edit. It allows the user to create subtitles with a suitable display duration, number of lines and characters, and reading speed – all of which are important factors that a translator must pay attention to when creating subtitles. Of course, it would be fun to translate the language actually spoken and display all those filler words (such as ‘um’, ‘uh’, ‘er’, ‘ah‘, and ‘like’). In this case, for some films or programmes, half of the screen would be obscured behind the subtitles.

Over time, professionals have developed a few general indicators to be taken into account on the technical side for subtitles. One of these is for the average duration for subtitles, or the time for which one subtitle is displayed on the screen. This is usually 1.08–7 seconds. Seven seconds may seem a very long time, and sometimes it really is, especially when the person whose speech is subtitled talks at a moderate speed. The situation becomes more difficult when the speech is either very fast or really slow. For example, if three people are excitedly arguing for seven seconds, there is simply no time to display their argument in its entirety. Another example is the opposite situation, in which the speaker struggles to complete a single sentence, one or two words at a time, for a whole minute. In such cases, the translator must be truly creative and find the best possible solution so that the reader can enjoy watching and understanding what is happening on the screen.

The next factor to consider is the number of lines and characters for each subtitle. Many people probably don’t realise that all the necessary content must be expressed in a certain number of characters and usually has to be displayed on the screen in chunks of no more than two lines at a time. This restriction is even tighter when one remembers that spaces count as characters. The number of subtitle lines onscreen is determined by the medium and the audience to whom the subtitles are directed. In most cases, a television screen presents subtitles in one language, over two lines; however, Estonian cinemas use bilingual subtitles on two lines, with the first line in Estonian and the second in Russian. The number of characters per line is set accordingly. On average, the maximum is between 37 and 40 characters. For subtitling, the nature and subject matter of the film, television programme, or other video being translated; the manner of speech; and the richness of the language all play a major role.

Why are these lengths and limits so important, and for whom? What is their purpose? The goal is to ensure that the viewer can easily read the text that appears on the screen without missing the last few words. Therefore, the translator’s work is dictated and limited by the reading speed. This is measured in characters read in one second. On average, it remains between 14 and 16 characters per second. If the presentation speed is significantly higher, the viewer may not be able to finish reading the subtitle. Translating a significantly slower conversation does not present major issues, as there is plenty of time to read the subtitles.

Fortunately, a translator can enter all of these parameters for the subtitling program, and if the specified values are exceeded or not taken into account, the translator gets notified immediately. For instance, it might warn that the sentence produced is longer than allowed. In addition, one can set default values for various little details, such as subtitle alignment and file format. Of course, what cannot be set, and where the real magic (and sometimes pain) of subtitling begins, is what to write in the subtitles.

Subtitling skills

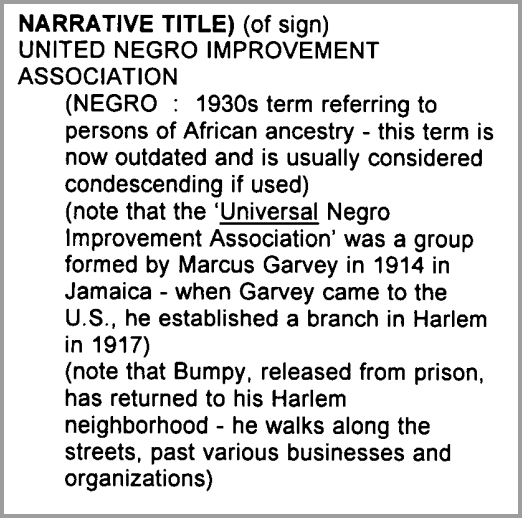

In general, the video files for films and series come with a script. The scripts vary in what they contain, and, depending on their thoroughness, they can make translation much easier. Sometimes the script even describes the characters’ actions, camera angles, emotions, and reactions. This information may be provided even if no-one on the screen is saying a word. In addition, it can be extremely helpful when the script explains the background, context, or special vocabulary of the production in greater detail. For example, the script for a historical film, in which the use of language may be unfamiliar to the translator, may explain certain aspects of it, terms, and abbreviations. This makes it easier to find a suitable match in the target language. Sometimes the words used at the time of the action depicted and their meanings are described very thoroughly. It also benefits the translator if information about the various institutions, organisations, groups, etc. is provided. All such clarifications aid in finding the best words for accurately conveying the idea to be translated.

(Example from Hoodlum)

Subtitling is similar to translating fiction. The ubiquitous colloquial speech that must be transformed into subtitles involves many expressions that don’t have a one-to-one translation for every linguistic and cultural space. Therefore, one could say that, in some ways, translating subtitles also involves localisation, or adapting concepts to another cultural space. If every occurrence of ‘damn’ in an English-language film were merely translated as ‘neetud’ in the Estonian subtitles, the end result would probably look rather awkward to someone following the subtitles. For a specific context, or the situation and surroundings, another word may be more appropriate. People on the big and small screen can often be heard swearing ‘Damn it!’, and we use the similar phrase ‘Kurat küll!’ in Estonian in such situations. The same is true of the curse ‘Jesus Christ!’, for example. While we do use ‘Issand Jumal küll’ in our cultural context, it isn’t quite as commonplace as equivalent phrases in foreign movies and series. Therefore, for the sake of variety and plausibility, most ‘Jesus Christ’s should be translated into Estonian as ‘Isver-susver’ or ‘Oh jeerum’. Also, the speech often involves various proverbs and idiomatic expressions that cannot be translated literally into Estonian. A corresponding local phrase should be found to convey the original meaning.

One aspect of translation work, which tends to be overlooked not only with regard to subtitles but also for translation and editing in general, is the broad knowledge base required. The translators need the same breadth and depth of knowledge that the selection of television shows and films covers. From cooking programmes to car repairs, from sports to nature documentaries, from history to horror films, each topic inevitably is accompanied by its own set of words, expressions, and so-called subculture, which may not be immediately obvious without personal experience in the field. When the translator doesn’t know what a certain word or phrase means, translating it is impossible. This is how the English word ‘Allen key’ may become ‘Alleni võti’ in Estonian even though the term should be ‘kuuskantvõti’. Anyone trying to search a construction or repair shop for Allen keys on the basis of ‘Alleni võti’ could waste a lot of time.

One shouldn’t complain about this challenge, though. On the contrary – when an editor or translator has questions and approaches colleagues for ideas, the results may be surprisingly beneficial for the entire team.

Regrettably, the quality of subtitles displayed on the screen today seems to fluctuate. Quite a few of the translation errors and inaccuracies that appear could have been easily avoided. There are several reasons for this. Generally, linguists have a lot of work to do, and spending too much time on any single project takes time away from other tasks. It also reduces the remuneration received. Also, in some cases, no-one is involved in the work process to check and edit the translation produced. There is simply no time or budget for an extra pair of eyes, as translation services are rather expensive.

Working as a subtitle translator or with consumer-oriented text? As a junior translator, I recommend that every new translator spend at least some time working with subtitles. Why? From my experience, I can confirm that translating subtitles helps one become more creative in the translation process and be less fixated on direct and literal translation. Also, having to adhere to certain instructions and limits (related to character counts, reading speed, etc.) helps you to find more understandable expressions, alternative wordings, and shorter ways of conveying lengthy thoughts. All this helps train a translator to create more comprehensible output, become more well-rounded, and avoid unnecessary verbosity and jargon.

The translation of subtitles undoubtedly deserves more attention in today’s translation market and, most definitely, better compensation. Skills in subtitling, work experience accumulated over time, and the resulting expertise should all contribute to an increase in the remuneration. For a beginner, translating subtitles may not be highly motivating at first. A novice translator lacks the vast base of knowledge and experience that more seasoned translators possess, so the work is slower. This, in turn, affects the total pay. The work speed only increases with time and practice, and the pay follows suit. Ability to distinguish between the essential and the insignificant comes only through experience. For some series and films, it doesn’t matter much whether the fish is a perch or a snapper. However, this does not apply for a nature documentary, and it would be just plain odd to describe Dory and Nemo from Finding Nemo in such a way (since the film identifies both characters by the full names of the species). Such choices might seem extremely simple, but reality is another story. In addition, the small size of the Estonian market plays a role here – only Estonians read and need subtitles in the Estonian language. For example, it costs the distributor of the series Game of Thrones exactly the same amount to subtitle it in Estonian and German, while the advertising revenue from the two translated versions is very different. Consequently, with the audience (or market) determining how much profit is available, Estonian subtitles face pressure to provide the service at lower cost. It is clear that big changes must start with small steps. Meanwhile, I hope I’ve helped with one of those small steps toward greater awareness and appreciation.

How to translate subtitles? We know the answer.

Contact us: info@interlex.ee